Was im Jahr 2013 noch als theoretisch galt, ist jetzt bewiesen. Mit dem Beweis der Zeitkristalle muss das bisherige Verständnis von Zeit grundsätzlich in Frage stellen.

"Das würde dann unser bisheriges Verständnis von Zeit ziemlich in Frage stellen", sagte damals der an den Experimenten beteiligte Physiker Tongcang Li. "Zunächst müssen wir aber beweisen, dass dies tatsächlich überhaupt möglich ist."

Was sind Zeit Kristalle?

Im Juni (2012) hatten Physiker um Xiang Zhang von der University of California in Berkeley die Herstellung eines Zeitkristalls in Form eines sich stets drehenden Ringes aus geladenen Atomen oder Ionen vorgeschlagen – eine Idee, die ein internationales Forscherteam um Zhang und Häffner in Berkeley nun in die Tat umsetzen will und hierfür derzeit ein hochkomplexes Labor aufbaut.

Die Hoffnung der Wissenschaftler war es, dass Zeitkristalle der Physik neue Wege aufzeigen können, wie sie die zwar präzisen aber immer noch unvollständigen Gesetze der Quantenmechanik zu einer größeren Theorie erweitern könnten.

Laut Einsteins Allgemeiner Relativitätstheorie (über Gravitation und die Struktur des Universums) sind die Dimensionen von Zeit und Raum miteinander in einer Struktur verwoben, die wir als "Raum-Zeit" bezeichnen. Die Quantenmechanik (die Interaktionen auf subatomarer Ebene beschreibt), stellt die Zeit-Dimension in einer anderen Form da, wie die drei Dimensionen des Raumes und erzeugt so eine Asymmetrie.

Laut Einsteins Allgemeiner Relativitätstheorie (über Gravitation und die Struktur des Universums) sind die Dimensionen von Zeit und Raum miteinander in einer Struktur verwoben, die wir als "Raum-Zeit" bezeichnen. Die Quantenmechanik (die Interaktionen auf subatomarer Ebene beschreibt), stellt die Zeit-Dimension in einer anderen Form da, wie die drei Dimensionen des Raumes und erzeugt so eine Asymmetrie.

Dieser unterschiedliche Umgang mit Zeit ist einer der Gründe für die Inkompatibilität zwischen Allgemeiner Relativitätstheorie und der Quantenmechanik. Um beide zusammenzubringen, muss mindestens eine der beiden verändern werden, um - so das Ziel theoretische Physiker - zu einer umfassenden Theorie über die Quanten-Gravitation werden zu können.

Wenn Zeitkristalle nun aber in der Lage wären, die Zeit-Symmetrie in gleicher Weise aufzubrechen, wie konventionelle Kristalle die Raum-Symmetrie, "so würde dies zeigen, dass in der Natur diese beiden Quantitäten ähnliche Eigenschaften haben und dass sich dieser Umstand auch in einer Theorie widerspiegeln sollte", erläutert Häffner. In einem solchen Fall wäre die Quantenmechanik inadäquat und es müsste eine bessere Quantentheorie gefunden werden, die Zeit und Raum sozusagen als zwei Fasern des gleichen Gewebes behandeln müsse.

In ihrem Experiment wollen die Forscher zukünftig versuchen, einen Zeitkristall dadurch zu erzeugen, dass sie 100 Kalzium-Ionen in eine kleine Kammer injizieren, die von Elektroden umgeben ist. Das von den Elektroden erzeugte elektrische Feld soll dann die Ionen in einer 100 Mikron (1/1000 mm = ca. Durchmesser eines menschlichen Haars) großen "Falle" einsperren.

Quellen:

-------------------------------

For months now, there's been speculation that researchers might have finally created time crystals - strange crystals that have an atomic structure that repeats not just in space, but in time, putting them in perpetual motion without energy.

Now it's official - researchers have just reported in detail how to make and measure these bizarre crystals. And two independent teams of scientists claim they've actually created time crystals in the lab based off this blueprint, confirming the existence of an entirely new form of matter.

The discovery might sound pretty abstract, but it heralds in a whole new era in physics - for decades we've been studying matter that's defined as being 'in equilibrium', such as metals and insulators.

But it's been predicted that there are many more strange types of matter out there in the Universe that aren't in equilibrium that we haven't even begun to look into, including time crystals. And now we know they're real.

The fact that we now have the first example of non-equilibrium matter could lead to breakthroughs in our understanding of the world around us, as well as new technology such as quantum computing.

"This is a new phase of matter, period, but it is also really cool because it is one of the first examples of non-equilibrium matter," said lead researcher Norman Yao from the University of California, Berkeley.

"For the last half-century, we have been exploring equilibrium matter, like metals and insulators. We are just now starting to explore a whole new landscape of non-equilibrium matter."

Let's take a step back for a second, because the concept of time crystals has been floating around for a few years now.

First predicted by Nobel-Prize winning theoretical physicist Frank Wilczek back in 2012, time crystals are structures that appear to have movement even at their lowest energy state, known as a ground state.

Usually when a material is in ground state, also known as the zero-point energy of a system, it means movement should theoretically be impossible, because that would require it to expend energy.

But Wilczek predicted that this might not actually be the case for time crystals.

Normal crystals have an atomic structure that repeats in space - just like the carbon lattice of a diamond. But, just like a ruby or a diamond, they're motionless because they're in equilibrium in their ground state.

But time crystals have a structure that repeats in time, not just in space. And it keep oscillating in its ground state.

Imagine it like jelly - when you tap it, it repeatedly jiggles. The same thing happens in time crystals, but the big difference here is that the motion occurs without any energy.

A time crystal is like constantly oscillating jelly in its natural, ground state, and that's what makes it a whole new form of matter - non-equilibrium matter. It's incapable of sitting still.

But it's one thing to predict these time crystals exist, it's another entirely to make them, which is where the new study comes in.

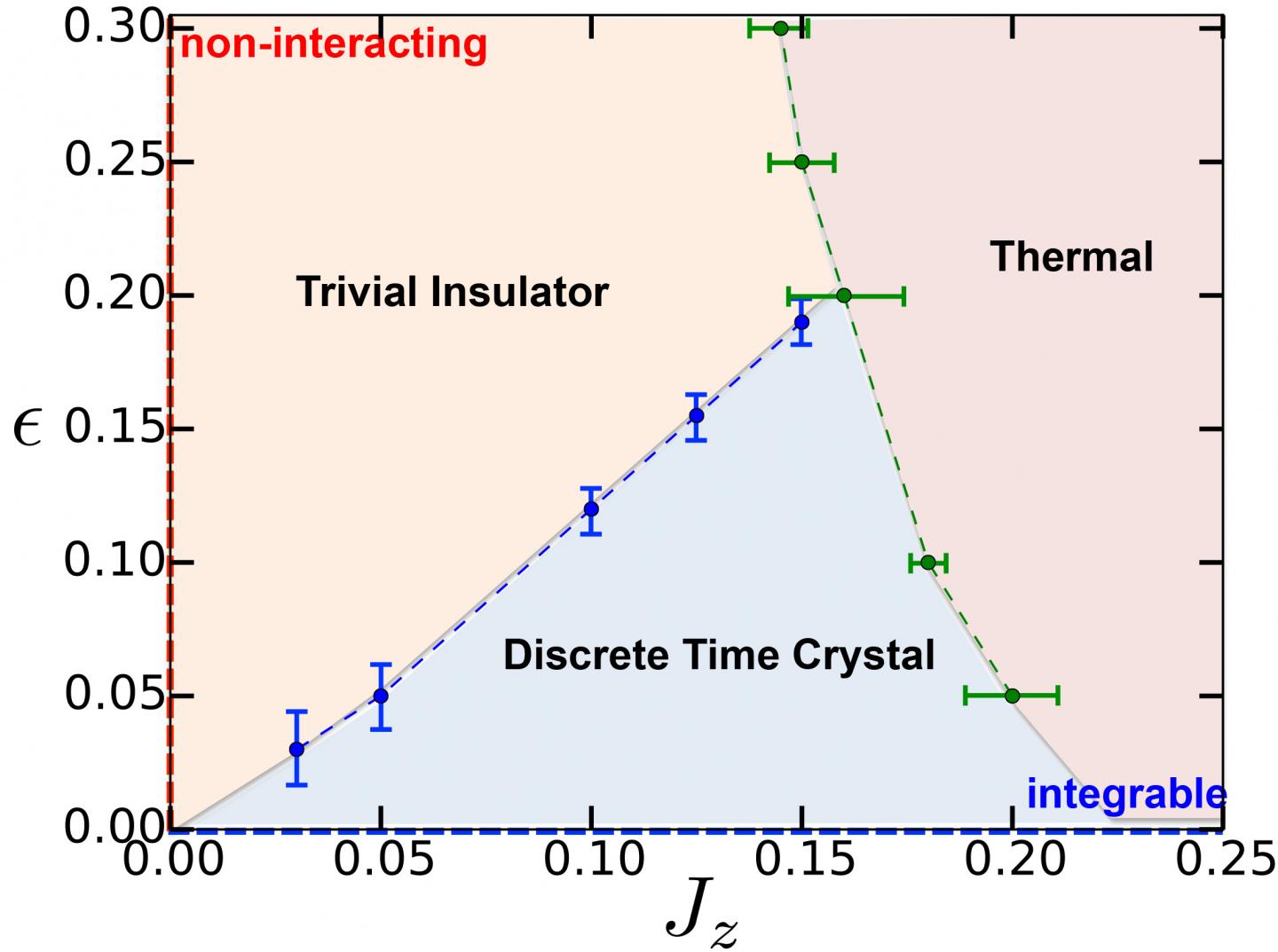

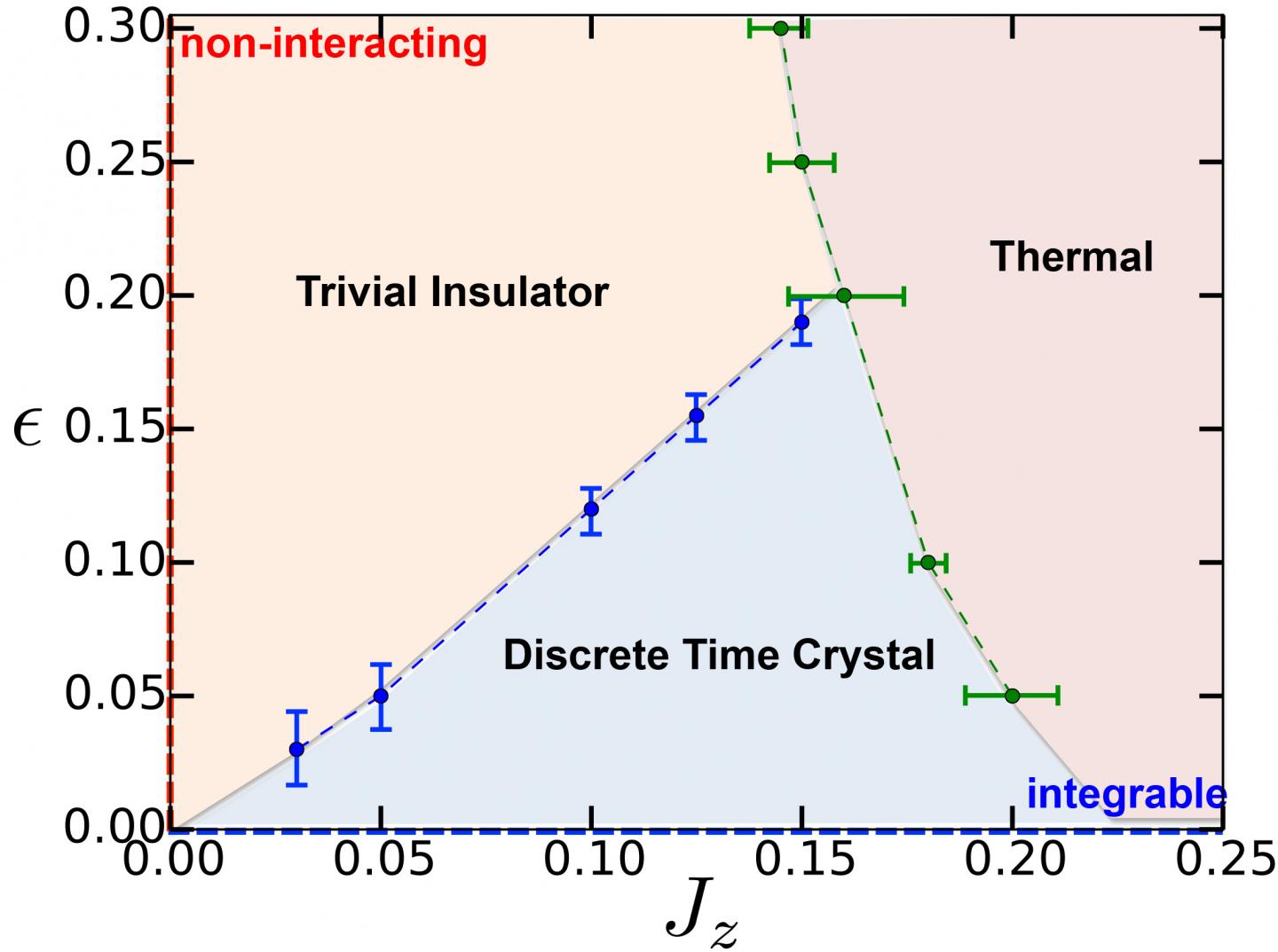

Yao and his team have now come up with a detailed blueprint that describes exactly how to make and measure the properties of a time crystal, and even predict what the various phases surrounding the time crystals should be - which means they've mapped out the equivalent of the solid, liquid, and gas phases for the new form of matter.

Published in Physical Review Letters, Yao calls the paper "the bridge between the theoretical idea and the experimental implementation".

And it's not just speculation, either. Based on Yao's blueprint, two independent teams - one from the University of Maryland and one from Harvard - have now followed the instructions to create their own time crystals.

Both of these developments were announced at the end of last year on the pre-print site arXiv.org (here and here), and have been submitted for publication in peer-reviewed journals. Yao is a co-author on both articles.

While we're waiting for the papers to be published, we need to be skeptical about the two claims. But the fact that two separate teams have used the same blueprint to make time crystals out of vastly different systems is promising.

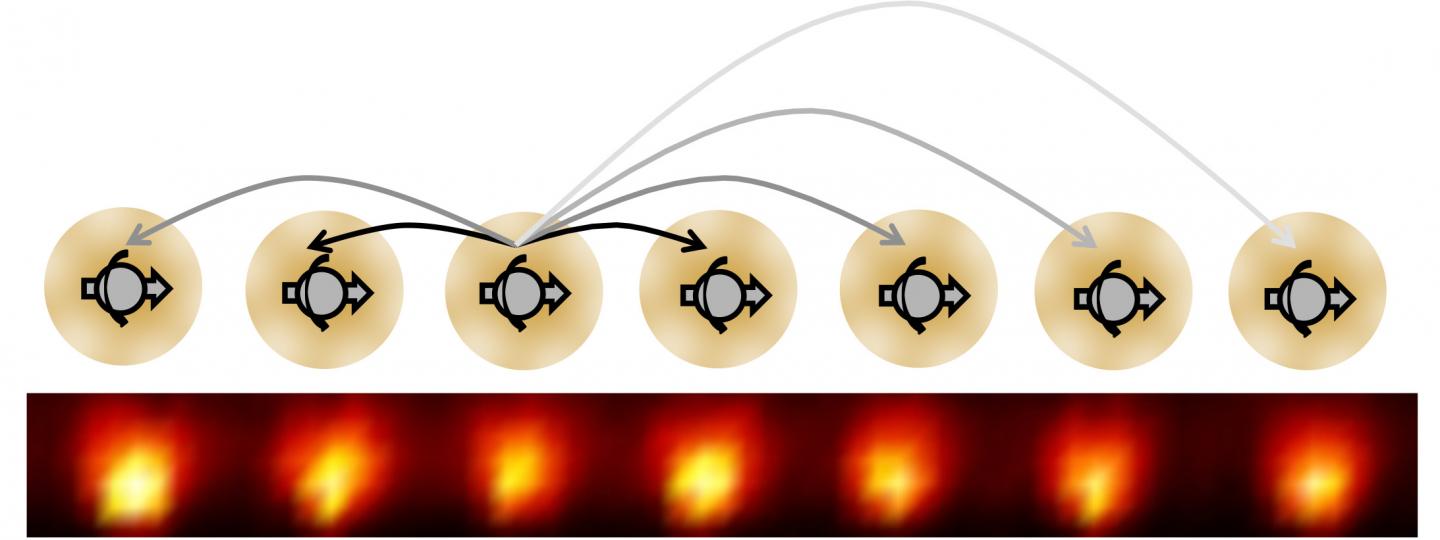

The University of Maryland's time crystals were created by taking a conga line of 10 ytterbium ions, all with entangled electron spins.

Chris Monroe, University of Maryland

The key to turning that set-up into a time crystal was to keep the ions out of equilibrium, and to do that the researchers alternately hit them with two lasers. One laser created a magnetic field and the second laser partially flipped the spins of the atoms.

Because the spins of all the atoms were entangled, the atoms settled into a stable, repetitive pattern of spin flipping that defines a crystal.

That was normal enough, but to become a time crystal, the system had to break time symmetry. And observing the ytterbium atom conga line, the researchers noticed it was doing something odd.

The two lasers that were periodically nudging the ytterbium atoms were producing a repetition in the system at twice the period of the nudges, something that couldn't occur in a normal system.

"Wouldn't it be super weird if you jiggled the Jell-O and found that somehow it responded at a different period?" said Yao.

"But that is the essence of the time crystal. You have some periodic driver that has a period 'T', but the system somehow synchronises so that you observe the system oscillating with a period that is larger than 'T'."

Under different magnetic fields and laser pulsing, the time crystal would then change phase, just like an ice cube melting.

The key to turning that set-up into a time crystal was to keep the ions out of equilibrium, and to do that the researchers alternately hit them with two lasers. One laser created a magnetic field and the second laser partially flipped the spins of the atoms.

Because the spins of all the atoms were entangled, the atoms settled into a stable, repetitive pattern of spin flipping that defines a crystal.

That was normal enough, but to become a time crystal, the system had to break time symmetry. And observing the ytterbium atom conga line, the researchers noticed it was doing something odd.

The two lasers that were periodically nudging the ytterbium atoms were producing a repetition in the system at twice the period of the nudges, something that couldn't occur in a normal system.

"Wouldn't it be super weird if you jiggled the Jell-O and found that somehow it responded at a different period?" said Yao.

"But that is the essence of the time crystal. You have some periodic driver that has a period 'T', but the system somehow synchronises so that you observe the system oscillating with a period that is larger than 'T'."

Under different magnetic fields and laser pulsing, the time crystal would then change phase, just like an ice cube melting.

Norman Yao, UC Berkeley

The Harvard time crystal was different. The researchers set it up using densely packed nitrogen vacancy centres in diamonds, but with the same result.

"Such similar results achieved in two wildly disparate systems underscore that time crystals are a broad new phase of matter, not simply a curiosity relegated to small or narrowly specific systems," explained Phil Richerme from Indiana University, who wasn't involved in the study, in a perspective piece accompanying the paper.

"Observation of the discrete time crystal... confirms that symmetry breaking can occur in essentially all natural realms, and clears the way to several new avenues of research."

Yao's blueprint has been published in Physical Review Letters, and you can see the Harvard time crystal paper here, and the University of Maryland paper here.

The Harvard time crystal was different. The researchers set it up using densely packed nitrogen vacancy centres in diamonds, but with the same result.

"Such similar results achieved in two wildly disparate systems underscore that time crystals are a broad new phase of matter, not simply a curiosity relegated to small or narrowly specific systems," explained Phil Richerme from Indiana University, who wasn't involved in the study, in a perspective piece accompanying the paper.

"Observation of the discrete time crystal... confirms that symmetry breaking can occur in essentially all natural realms, and clears the way to several new avenues of research."

Yao's blueprint has been published in Physical Review Letters, and you can see the Harvard time crystal paper here, and the University of Maryland paper here.

Quellen:

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen

Bei Kommentaren bitten wir auf Formulierungen mit Absolutheitsanspruch zu verzichten sowie auf abwertende und verletzende Äußerungen zu Inhalten, Autoren und zu anderen Kommentatoren.

Daher bitte nur von Liebe erschaffene Kommentare. Danke von Herzen, mit Respekt für jede EIGENE Meinung.